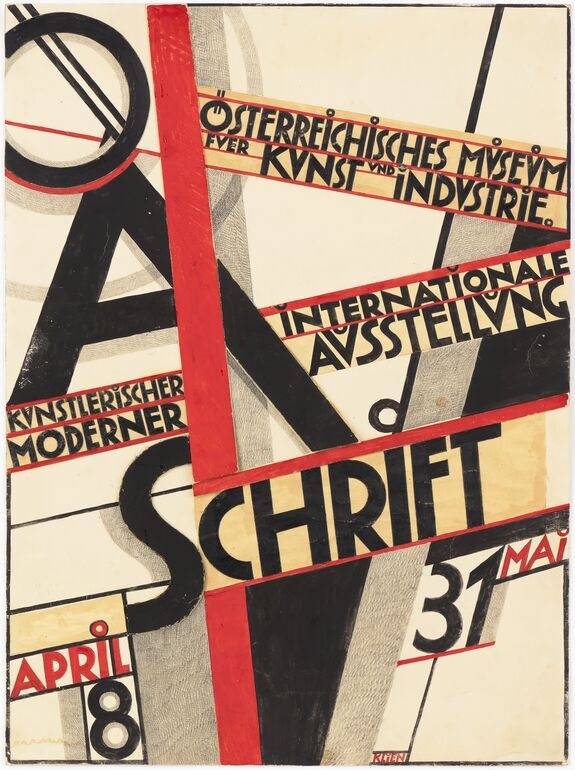

Vienna 1900 / From a Viennese Style to an International Style

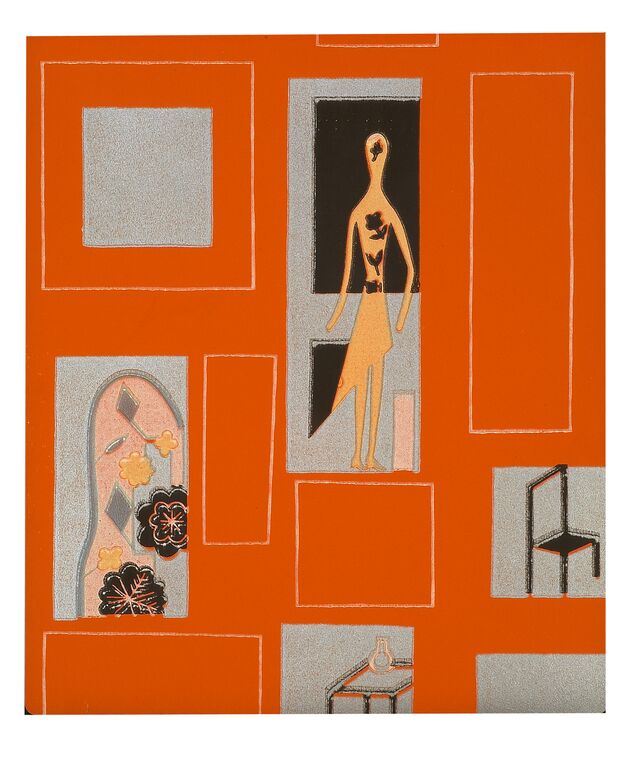

The heterogeneous world of objects in Austria between the wars differs from previous eras both in terms of when it emerged and its stylistic diversity. This diversity arose from an increasingly democratic attitude that accepted individual needs and thus appealed to different groups of buyers. The social upheavals after the First World War presented modernism with new challenges: in addition to new forms of representation, solutions were also developed for previously neglected social groups, often based on standardized industrial production—an area that museums only recognized as worthy of collection in the 1990s.

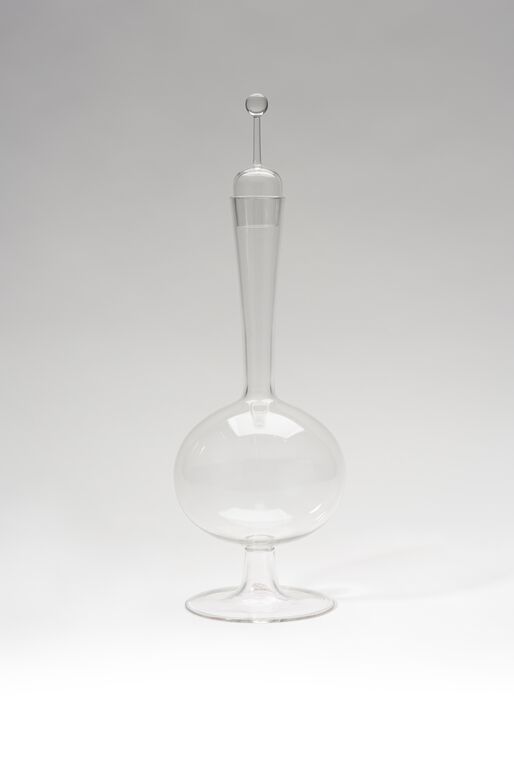

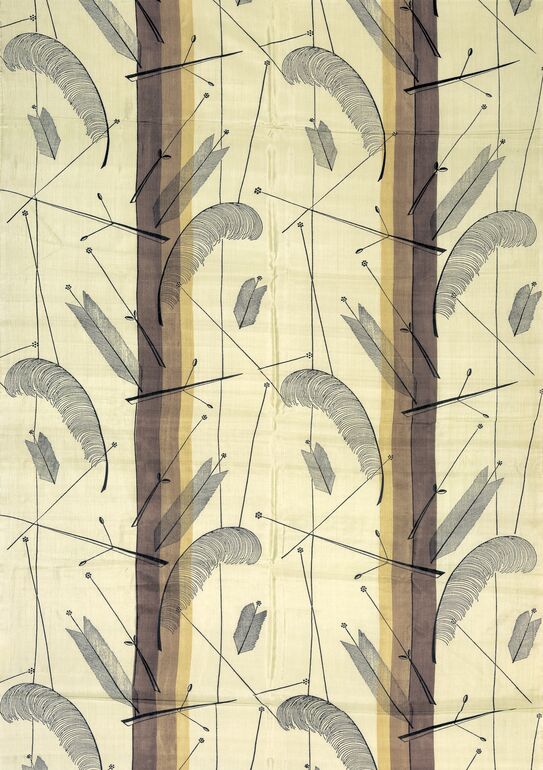

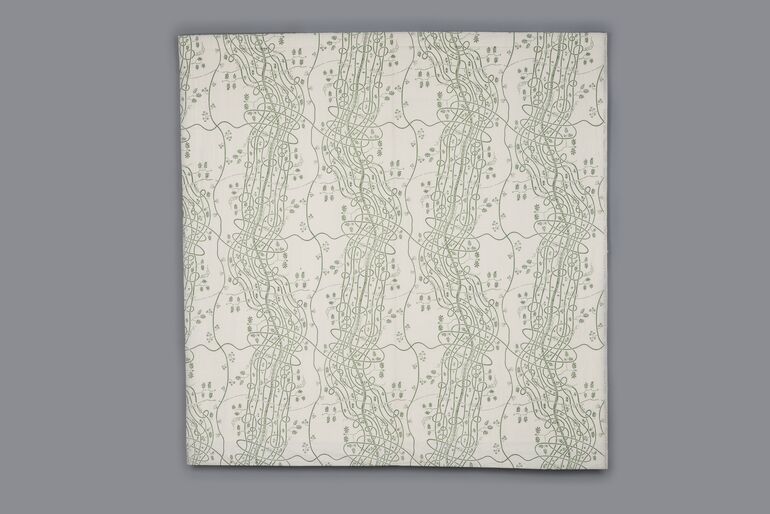

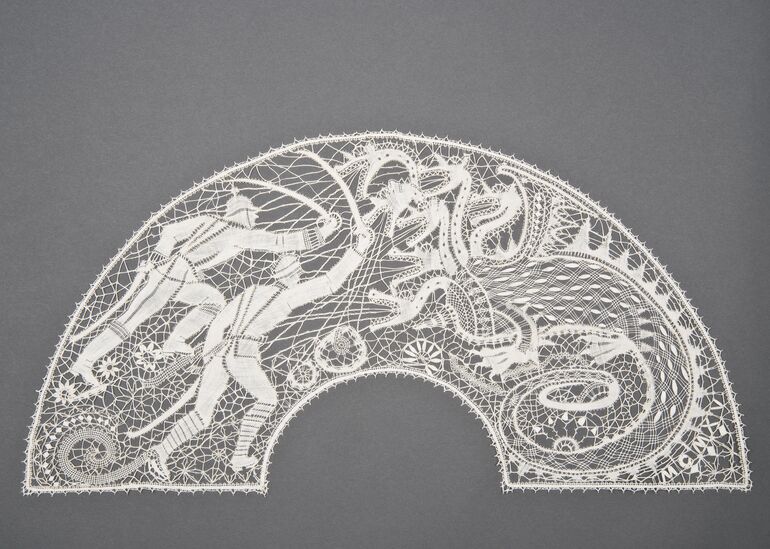

Although a new generation of designers in Austria represented the forms of international modernism, the Arts and Crafts tradition of exclusive craftsmanship, shaped by the Secessionists, remained alive, in contrast to Germany. One example of this are the elaborately crafted objects created in 1934 for the exhibition Das befreite Handwerk [Liberated Handicraft], which were produced in response to the modernist, industrial-oriented Werkbund exhibition shown in 1930.

Although the idea of the unity of the arts had lost its significance, the associated commitment to quality, combined with Loos’s cultural criticism, led to a specific Viennese manifestation of the transition from the Viennese style to the International Style. Josef Frank’s statement, “Steel tubing is not a material, but a worldview,” illustrates this attitude. With the Nazis taking power in 1938, this unique Viennese design language came to an end, as totalitarian regimes suppress individual forms of expression.

![[Present of Honor] from the Wiener Werkstätte on Josef Hoffmann’s 50th Birthday](https://mak-media.azureedge.net/s/697069849063de68751ca00e2250d8fa.jpg)